Old Dan

by Dan L.

Hollifield

Old

Dan lived up on th’ ridge somewhere—Some said it’us near Eagle Bluff,

some said

further off towards th’ lake, but it’us well away from th’ usual

stompin’

grounds of th’ city folk who hunted up thataway. Nobody knew quite

where... I

hear tell that th’ Sherriff knew how to find his place, but only ever

went up

there alone—and even then, only when he needed th’ old man’s advice or

help.

There was stories, you see, ‘bout th’ old man on th’ ridge. He showed

up at th’

General Store in Jacksboro for supplies ‘bout once a month. Sometime at

weddin’s, sometimes to attend funerals, once or twice when a new baby

was

baptized—didn’t matter which church, if Old Dan graced your service,

you

counted yourself blessed. ‘Cause you felt you were.

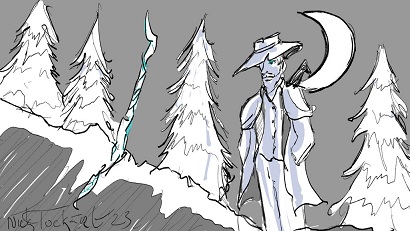

He’d

come walkin’ into town, pair of dogs at his heels, wearin’ a big,

hooded wool coat

like a mountain man would in cold weather or rain, well-worn overalls

underneath, and big boots on his feet. He had a gray beard, and long

silver-gray hair tied up in back like a Cherokee. Had a hat that looked

like it

could a come straight off a Rebel soldier or a riverboat man. That hat

done

seen some years, I’ll tell you. But it was clean,

if a little worse for

wear. Sometimes, he had a tall walkin’ stick made out of a Hickory

saplin’.

He’d

buy his vittles at th’ store, maybe trade the grocer-man a fine mess o’

watercress, or spinach greens, or a sack fulla fresh-picked corn for

some of

it. Always paid in cash, or old coins… Then he’d put his groceries away

in a

big ol’ one-strap oilskin sack he’d throw over his shoulder, and he

walked out

of sight back towards th’ ridge. Polite man. Quiet, too. Soft spoken,

but he

had an eye for th’ ladies—made ‘em feel special when he offered a word,

tipped

his hat, and he’d made more than a few of ‘em blush from a quiet remark

and a

gentle smile. And that voice of his was like magic—like silk on bare

skin—many

a fair maiden wished it was still fashionable t’ swoon when he

sweet-talked

her…

Nobody

knew who his family was. Nobody knew how long he’d lived up on th’

ridge. And

nobody knew for sure just how old he was. He was

just always there,

somewhere around, like the hills themselves, or the rivers, or the oak

trees on

the mountains. But all th’ same, people stayed away from where they thought

his house was. Especially after that time th’ Revenue Men came runnin’

back

down off th’ ridge like they was bein’ chased by a bear.

Seems

they’d a-thought he must be runnin’ a still up there. Well, maybe he

was, but

nobody ever claimed to of bought any liquor offa

him. So they marched themselves

on up t’ th’ ridge, with their dogs and their guns and their shiny

badges—and then

come a-runnin’ back down like th’ Wrath of God was behind ‘em with th’

Flamin’

Sword, like right out a th’ Bible. Ol’ Dan turned their guns and badges

in to th’

Sherriff when he come down th’ ridge himself a week or so later. Said

they must

a throwed ‘em down to run faster from whatever they’d a-thought was

chasin’

‘em. Said his dogs was barkin’ up a ruckus that evenin’—fit to chase

off a

mountain lion, he said—and he’d found th’ shootin’ irons and tin stars

a-layin’

around on th’ trail when he next come down to go t’ town. Like he was

just

pickin’ up the trash left behind by careless hunters. Th’ Sherriff was

always

respectful to Ol’ Dan.

A

few of the Revenue men told stories about comin’ up to a place on the

ridge

where the native rock grew out of the ground like the pillars of some

ancient

temple—half was melted and the other half hand-hewn—but hewn by whose

hands?

Human hands? Or Other? Some talked of a small house

and a garden, and

the sounds of a party in full swing. Or a quiet mansion surrounded by

the feelings

of good will, peace, and contentment. Still others talked of guard

dogs—or were

they bears? Or wolves the size of bears? Some wished to return, under

other

circumstances, to join that party they thought they’d heard. Others

moved

away—way out West to the empty spaces of the desert where they could be

sure

that nothin’ was sneakin’ up on them. And still others chose to retire,

to move

up to the ridges and valleys of the Smoky Mountains in search of some

kind of

peace and fulfillment inside themselves that they never knew they

needed until

that night…

Th’

old man always turned up for search parties when somebody went missin’

in th’ woods,

or out by th’ lake. Him and his dogs would join th’ party, and almost

always

found th’ path where th’ folks got lost. Sherriff said they was good

huntin’

dogs, that’s all. Nobody ever said a bad word about th’ old man. He was

kinda stand-offish,

but kind and generous to everybody.

Now,

he did once have a throw-down with that so-called travelin’ Preacher

that come

through—and people was sayin’ Preacher was getting’ handsy with some of

th’ children.

Ol’ Dan showed up at th’ Preacher’s revival tent unexpected-like one

evenin’,

dressed in his finest Sunday-Go-To-Meetin’ clothes. An old suit that

was clean,

if a tad out of style, with a starched collar, and one a them-there

string ties

them Kentucky Colonels like to wear. Looked downright impressive, to

hear tell.

Took

th’ stage t’ stand by th’ lectern without any warnin’, and proceeded to

give

one of th’ most Hellfire and Brimstone sermons anybody could recollect ever

hearin’. Started off with “Suffer Not Th’ Little Children” and went on

about

how th’ Fiery Pit was ready for them that dares lay a hand on th’

Lord’s Precious

Little Angels—all th’ while givin’ a look to that Preacher that would a

made a

platoon of hardened soldiers quake with fear. Everybody was a-waitin’

on th’ lightnin’

to fall down on that Preacher—th’ old man’s sermon was that

powerful.

Preacher packed up in th’ middle of th’ night and run off to further

pastures—and

left his tent behind. Th’ fact that Ol’

Dan’s two dogs went onstage with him and sat—unbidden, to either side

of the

old man’s feet, showin’ their teeth to that preacher, an’ quietly

growling a

warning—didn’t do anythin’ to gentle th’ stories afterward none. Those

dogs got

respect from th’ people, too.

About

them dogs… People said they was part wolf, maybe mostly

wolf—or looked

it, anyways. They was waist-high at the shoulder, and muscled like a

full-growed bull, and walked like they was th’ Wrath Of God, incarnate.

Children wasn’t afraid of them. Th’ local ne’re-do-wells feared ‘em,

and th’ would-be

toughs did too. One dog was dark brown, t’ other was black, both

long-haired,

and generally looked like them German Po-lece dogs, but th’ biggest

you’d ever

seen in your life. Th’ old man didn’t have to give ‘em commands. Just

clicked

his tongue and pointed, or just pointed without sayin’ a word,

and th’ dogs

went and did what he wanted ‘em to go and do—like they was a force o’

nature,

but his to command. They didn’t frighten cats,

neither. Th’ old man

attracted cats like a magnet tugs on cold iron. But th’ dogs never even

growled

at ‘em. Nor they them, in return. Cats loved th’ old man. Birds too,

but that

was spooky... He named th’ dogs Thunder and Lightnin’. Thunder was th’

brown

dog. Lightnin’ was th’ black one. They was always around th’ old

man—even when

you couldn’t see ‘em nowhere near. Some young tough’d start to give th’

old man

trouble, and them dogs come outa nowhere—like storm

clouds comin’ out

from behind th’ ridge to drop a summer squall—or a tornado. They was

always

quiet too, leastways lest they wanted to be loud,

and then they

growled like a lynx th’ size of a bull. Ain’t nobody alive wants to

hear that

sound. No sir-ee!

Now,

about those stories ‘bout th’ old man… One I heard tell of once

concerned th’ day

one of th’ local coal mines had a whole gallery collapse. Right about

shift

change, th’ night workers shuffled out lookin’ for their fellows on th’

day

shift, and found a rockfall blockin’ th’ road out and in. Nobody heard

the

rockslide in th’ night. Nobody felt it happen, neither. It was just there

that mornin’—like it’d always been there, right

across the only road t’

th’ mine. Everybody got delayed goin’ home or comin’ in.

Nobody

was the least bit happy ‘bout it… Then they heard

th’ cave-in a-groanin

and a-boomin’, and dust come a-boilin’ out th’ mine entrance like th’

hateful

breath of th’ Devil his-self. Four of th’ miners were still inside, but

over

fifty was out—day and night shifts alike. One of th’ miners up topside

claimed

he saw Ol’ Dan standin’ way up on th’ hill from where th’ rockfall

happened.

But then, like magic, he was there in amongst ‘em,

takin’ charge and

givin’ orders like he expected to be obeyed—like he was in command all

of a

sudden. And th’ men found they was doin’ it,

whatever th’ old man said

to do. His quiet voice carried to every ear.

Whatever he said had th’ impact

of th’ Gospel, itself, and everyone there pitched in to clear th’ mine

entrance

so that th’ men trapped inside might have a ghost

of a chance of

getting’ out alive. I hear tell th’ old man waded in himself, throwin’

rocks

aside like they was so much sponge-cake. Th’ dogs was there, a diggin’

and a

scratchin’ at th’ rocks right next to th’ old man—and it seemed like

half th’ cats

in th’ county, too. There was even talk of an eagle flew down and

started

scratchin’ at th’ rocks like a chicken—flingin’ rocks out th’ way.

‘Twern’t

long before everyone knew they’d need even more

help to save those men

inside th’ mine. Runners set out to alert th’ townsfolk—but that woulda

took

some time. Then th’ old man called th’ crows.

Way

I heard it, soon as th’ runners set out, th’ old man stood up

straight—taller

than anybody ever remembered him to be, grabbed his walkin’ stick and

jabbed it

into th’ ground like it’us a fence post. Sparks flew from th’ tip of

th’ stick

when it struck th’ rock. Th’ old man tipped his head back, and started

cawin’

like a crow. His voice echoed from th’ hills and ridges, getting’

louder and

louder… Then th’ crows came. They came up like a thundercloud,

darkenin’ th’ sky

in their multitudes, circlin’ like a tornado—then split to head for all

th’ nearby

towns. Like rivers of ink in th’ cloudless blue sky, they set up such a

ruckus

in th’ towns that people just had to come outside and see what was th’

matter.

And they came, following th’ path th’ crows marked out, until every

able-bodied

soul for miles around started headin’ for th’ mine.

Long

story short, there was soon near a couple hundred folks at th’ mine,

clearin’

away rubble until th’ men inside were able to crawl out. Not one life

was lost

that day. By th’ time th’ last man got out, th’ birds were gone, and

when folks

began to look around for th’ old man, well—he was gone too. But his

stick was

still set into th’ ground, as unmovable as an oak tree, stout as th’

old

Hickory it’us made from. Nobody could budge it an inch. Then th’ mine

gave an

almighty groan as another collapse hit its halls. Coal dust and dirt

boiled out

like a chokin’ cloud. When folks remembered to look at th’ stick once

more, it’us

gone without a trace. Like a dam blockin’ a mighty river, when th’

stick was

removed, th’ mine collapsed completely. Not one

life was lost, that

day.

There

was another story. One time, a little girl of about 12 years or so got

caught

in a sudden snowstorm up on th’ ridge where she’d gone berry-pickin’

for her

Granny to make a pie for th’ family’s Sunday dinner. People searched,

but

couldn’t find her. As it got too dark for even lanterns to guide their

steps,

they heard what they thought was wolves howlin’ in th’ distance. They

shuffled

home in th’ growing darkness, heads downcast, bereft of hope for th’

safe

return of their little girl. Th’ family spent a sleepless night in

prayer for th’

safety of their daughter. Churches held all-night vigils, likewise in

prayer,

until dawn of th’ following day. Came th’ sun th’ next day—even before

th’ townspeople

could once again set out to search, Old Dan in his heavy woolen coat

came

striding into town, big boots crunching th’ fresh snow with every step,

dogs

aside him, as he made his way to th’ home of th’ family of th’ missing

girl.

His coat was tied tightly about his waist, its sleeves empty, and his

dog Thunder

stood on hind legs to knock on th’ family’s door. Th’ mother of th’

girl

wrenched th’ door open as if she was want to tear it off its hinges.

Without a

word, Ol’ Dan went in, opened his coat from the inside, and laid th’

little

girl on her Granny’s feather bed. Covering her with a thick blanket, he

turned

and softly spoke to th’ mother and grandmother and father.

“Don’t

try to wake her,” he said. “She’s in a healin’ sleep. She’ll want

feedin’ when

she wakes tomorrow mornin’. Give her whatever she wants, but please

make sure

she drinks this potion afore she eats anything.” He handed the mother a

tall,

old medicine bottle—like from the days before the Great War. “It’s just

herbs

to help her body heal from th’ cold. She’ll be tired for several days.

She’ll

eat like a horse, she’ll sleep a lot for th’ next few days, but she will

heal—Completely. She won’t remember what happened after th’ snow began

to fall.

She won’t remember my finding her, takin’ her to m’house or feeding

her, or

giving her a potion to help her sleep without pain. She told me her

name was

Aurora, but I know you named her Beverly—after her great-grandmother.

Fine

woman. Did real good for herself. Call the girl Aurora from now on. She

chose

the name. It suits her. She’ll never be sick another day in her life.

She’ll

grow to be a strong woman. She’ll find a good man to wed when she’s

grown—I’ll

see to that! Oh, she’ll give you no end

o’ trouble ‘til she takes

a husband—after that he’ll have to watch his own

steps! When th’ school here

has taught her everything it can, tell her that I am willing to teach

her

herblore and medicine and all manner of practical things—but only if

she so

chooses to learn those. Her life shall ever be her own, but for now,

she is

under my protection. Blessings be upon this house,

and to all who will

dwell within it. Forever and ever… Amen.” With that, he bowed to th’

father,

bowed to th’ mother, and took th’ grandmother’s hand, kissing it. “I

remember

thee, Rosemary,” he said to her. “Thy pecan pie is worthy of th’ Gods,

themselves. You have ever been blessed, in my memory, and in th’

memories of th’

Others. When your Work is done, I will remember thee. For all my days,

I will

remember thee. Did I not tell thee once that thou will have a long and

happy

life, Granddaughter? I see that thou hast, indeed, gained everything

thou

wished to have. At th’ end of days, my house is ever open to thee—if

that is

still thy wish…”

Then

he left. Back into th’ snow, dogs at his sides, to return to th’ ridge

above th’

town, until needed again…

That’s

just a small sample of the stories surroundin’ Ol’ Dan. Where he came

from, when

he came from, where his house on the ridge is, why he does what he

does, how

he does what he does… No one knows. Maybe he was there when

the sun first ever

shone over the Smoky Mountains. Maybe longer. As to why

does he cares so

much about his neighbors? Maybe the clue is in his name… Old Dan, Ol’

Dan, Ol’Dan,

Odin? Perhaps… If so, then who are The Others the

old man spoke of?

Maybe,

just maybe,

if we’re really lucky, if we’re kind and gentle and

compassionate—magic

is loose, in the world, tonight…

THE END

© 2023 Dan L. Hollifield

Illustration © 2023 Nick Tockert

Bio: Dan L. Hollifield is a

writer, composer, artist, and the Senior Editor & Publisher of

Aphelion Webzine. He lives out in the countryside near Athens, GA with

his wife, her dog, and several cats. 2023 will see his final year of

gainful employment at a local factory after 46 years of working there.

He has two books of his own on Amazon, as well as several short stories

in various anthologies published both here in the US and in Europe. He

currently has nine albums of instrumental music available on his

Bandcamp page.

E-mail: Dan

L. Hollifield

Website: Dan

L.

Hollifield's Author Page On Amazon

Dan L.

Hollifield's Bandcamp Page

Comment on this story in the Aphelion Forum

Return to Aphelion's Index page.

|