I tell no one, afraid they will think me insane. (There is even an ordinance in this area that limits the height of buildings such as ours to seven stories. My hallucination is illegal!). And insane is what I feel as, wallowing in indecision on the beach like some kind of fool, I stare for close to an hour, all the while hoping that this will prove to be tired eyes matched against overworked emotions--lately my days have been filled with anxiety, depression and fear--I am upset and cannot remember when or why it started. I know it must relate somehow, unexplained and tormenting emotions and the hallucination, but the how of it escapes me. Perhaps the former brings about the latter.

I do know one thing, however: There is something on that floor that terrifies me.

How I wish I could confide in a friend, someone who might, however much he or she questions my mental health, accompany me on a visit to my fantasy--it beckons me in a way that I find difficult to resist. But having just entered my ninth decade, there are precious few friends left, certainly none who would not first consider the ravages of time upon an ancient mind.

The building's elevator weighs in on the side of reason, in its buttons and in its electronic displays; both testifying to only seven floors. I do not accept this as final, however; I invent a penthouse owned by someone who does not wish to tempt commoners such as I to come calling. Even so, I hesitate. I am reluctant to go, even as I more fear not going than going.

My sigh is a fatalistic one as I wait for an opportunity to present itself, one that does not include witnesses, then make my way across the seventh floor corridor to the heavy fire-door that bars entrance to the building's stairwell. Once there, I open it just far enough to listen, then, hearing no traffic, pass through and close it firmly behind me. There is a set of stairs leading upward, but this is neither a surprise nor a confirmation; it provides access to the building's flat roof. Less inclined toward stairs at my age, I move with difficulty to the point where the bend in the landing permits a tentative look around the corner, tentative because I fear an encounter with a workman. I imagine my expression as I struggle to explain. But the way is clear, and I continue my climb toward uncertainty, at the top pausing to press an ear against the door--I need to know what lies on the other side but am reluctant to go that extra mile. In time, after constructing a story to hurl at whoever may interrupt me at my moment of indiscretion, I assume a look of confusion--it comes too easily these days--then turn the knob.

I am unprepared for the darkness that greets me on the other side of the door. Something is wrong; this should not be. Like other stairwells in this building, this one should open to an outdoor corridor bathed in sunlight. With my confused expression now more genuine than contrived, I stretch my upper body across the threshold and command my senses to penetrate the black void. This produces nothing, and I venture further into the room, forgetting for the moment that I am supporting a heavy fire-door, my only source of light. It closes with a suddenness that disturbs the rhythmic beating of my heart.

At that exact moment, as if connected to the door, the lights come on. I am in an outdoor corridor richly bathed in sunlight.

I have little time to reflect on the oddity of this as someone turns the corner at the far end of the corridor then heads directly for me. It is a young man, and there is enough familiarity about him to tell me I am right about this floor--if I have seen this person, my neighbors must have seen him as well. The clothes he wears are less familiar, however. They suggest something out of a grade-B science fiction movie, a one-piece suit, skin-tight to the point of discomfort yet flaring out at the shoulders and just below the knees where it ends.

I notice a hesitation in his step, and this encourages me to ready my cover story, what it was that "accidentally" brought me to this floor. I hold off delivering it as I see a lack of focus in his eyes; he is looking not at me but at the heavy door that so recently banged shut. I watch as he issues a shrug of dismissal then resumes his rapid pace, a pace that soon brings me to think he is intent on running me down--I am forced to jump aside at the last moment to avoid contact. I cry out in protest of such rude behavior, but only receive more of it in turn. He continues on his way, opening the fire-door then passing through to the stairwell.

The weight of too much happening with too little of it being explained brings me to a quick boil, and I grab at the door intent on letting the young man know how I feel. As I yank it open, the corridor retreats into darkness, bringing me to wonder why the same thing did not happen when my rude friend passed through. Regardless, although there is as much light in the stairwell as there was on my trip up, he is nowhere to be seen.

An odd feeling sweeps over me, one that suggests I am not meant to be here, that if I do not soon leave, I will cease to exist. I hurry through the opening then down the stairs then through the door offering access to the seventh floor, my floor, supposedly the top floor of this building. As the door closes behind me, I lean with my back against it, as if in doing so I can save myself from whatever it was I was fleeing.

Almost immediately, someone pushes against me from the other side.

I move with greater speed than I thought capable of a man my age then swing around to face the door, my hands thrust out protectively in front of me and my mouth and eyes stretched to the limit. It offers testimony of senility to a neighbor who, after hesitatingly asking after my health, moves quickly down the corridor.

Night falls, and it blackens my world in a more traditional way, yet I find it impossible to sleep. I sit in my darkened parlor, stare out the window and see only my inner thoughts. Although time encourages me to try, I can attach no rationalization to the unfathomable lighting, the futuristic costume and, of course, the eighth floor itself. The night is threatening to become morning when finally I surrender to my emotions and descend to the beach, there to stare up yet again at what the healthier part of me knows is an illusion.

A single light shines in the condo directly above mine, but nothing moves within its glow. I back toward the ocean, uncaring that I am entering the surf as I struggle to get a better angle. That light has to reveal something, furnishings if not people. It does me no good; I see only the faint hint of a sculptured ceiling not unlike my own.

When the sun rises and brushes away the night's unreasonable fears, my curiosity revives to the point where I can again move with purpose toward the forbidding stairway. Thinking it might make a difference, this time I enter it at its lowest point then faithfully count floors as I struggle upward. To someone my age, this is a monumental effort, but I take solace in the realization that the physical exertion is taking the edge off my fear. I long for a final count of seven, and thus an end to this madness, but it does not happen. I continue up an eighth flight of stairs, knowing it will lead, not to the roof, but to a place that exists only in my mind.

The world again fills with daylight as I close the heavy fire-door behind me on the eighth floor. This time it is a woman I see, a woman in her early thirties, a woman who, like the young man of yesterday, is familiar yet not so. She is stunningly beautiful and wears a red, short-sleeve, thigh-length dress that confuses me. Far from futuristic, it is out of the twenties, a time when women revealed almost as much of themselves as they do today. Having lived through that era, I find this appealing. In one hand she carries a pocketbook and in the other a briefcase, the latter an incongruity when compared to the way she is dressed. The briefcase is modern, something a salesman might carry, large enough to store manuals and samples.

Captured by her beauty, I feel no inclination to retreat back down the stairs. Instead, I watch with obvious approval, even as it becomes clear to me that she does not notice-she is looking beyond me at the door that has just banged shut, her look saying she expected someone to emerge. Her interest only fleeting, she turns and begins moving away, intent upon a destination that now becomes mine as well.

I am the willing victim of a lovely pied-piper who unknowingly leads me, not unsurprisingly, to the condo directly above mine-I try without success to remember the sound of her feminine steps on my ceiling. When she enters she does so with a key, closing the door afterward before I am able to follow. Even so, I make no cry of protest, less afraid of startling her than of having it confirmed to me that she cannot hear, that on this floor I do not exist. Instead I move to a nearby window, arriving just in time to watch her drop keys and pocketbook into a wicker basket perched upon a modern sofa table.

She is not alone. There is a man half sitting, half lying on the sofa at the far side of the living room, an absolutely ancient man who seems to share the inclination of the people of this floor toward odd clothing. He wears a tuxedo, complete with frilly shirt, dark bow tie and matching cummerbund. His dark black shoes are immaculately shined. I get the impression that, even at this early hour, he is prepared for a night out, perhaps the most important one of his life.

As with the other people I have encountered on this floor, there is a haunting familiarity about him, one that brings a chill to my bones as I struggle to understand why. Certainly if I had seen him dressed as he was at this moment; I would find him impossible to forget.

The young woman, still carrying her briefcase, moves to his side and assists him in sitting up. He is appreciative of the help and likely needed it--I watch as a smile crosses his face, a weak smile, sad as well as if he believes this is the best he can expect from this encounter. After a short conversation, which I have no chance of hearing, she opens the case then, in a professional manner, begins spreading its contents around the coffee table. All but one piece is unrecognizable. The one familiar item is a stethoscope which she soon puts to use. I think by this that she must be a doctor or a visiting nurse, an easy assumption considering the age of the person she is attending. Certainly she is not a lover. I watch as she places the stethoscope to his chest, listens quietly for a few seconds then straightens up. When her mouth begins moving, I can tell by the somber expression on her face that her words are not easy for the old man to listen too. The shaking of her head and the intensity with which she watches his eyes only confirms this suspicion. The old man's response is a deep breath and a stoic smile, powerful indicators of the nature of the news he has received. I feel a moment of nausea as I watch the woman reach into her briefcase and extract a syringe.

I know then that something is going to happen, the "something" I did not want to see. I tell myself to leave this place even as, like a child, I press my face against the window to see more clearly what will happen next. I do not even blink as she touches the syringe to the old man's neck then presses it into his flesh--he twitches slightly but otherwise does not react; he is trying his best not to. Something is said, first by her then by him, then she releases whatever it is the syringe is holding.

The old man immediately falls to one side.

The suddenness of this catches me off guard, and I cry out to myself that I have it all wrong, that I am permitting confused emotions to color reality. But when I search for assurance that the old man is still alive, I see not the slightest swelling of his ancient chest.

The nausea within me builds as I switch concentration to the young woman, hoping to see in her face what I did not see in his, that all is well, that her patient is enjoying no worse than a prescribed rest. I see nothing there to suggest she is feeling anything but satisfaction for a job well done. There is even a smile, although one with a hint of sadness attached to its edges. Seconds later she is gone from my sight, and I realize by this that she has entered another room, a bedroom or a bathroom.

Minutes lead to an hour, yet my eyes do not stray from the motionless form on the sofa. I continue to search for movement: shallow breathing, a twitch of agitated skin, proof that life still exists within that ancient body. I did not want this to happen; I do not want it to be true even now, when there is no longer a doubt. I slam my fist into the window, only partly surprised when it proves to be solid to my touch. Although invisible to my fellow humans, I am obviously not so to the condo itself. I strike at the window again, then again, then repeatedly without pause, all of this without reason or purpose. I know only that I am soaking in emotions that include guilt and pain, and that I must punish myself against this inanimate object.

I stop when I hear movement inside. Someone is coming, someone who, by the sound of his grumbling, does not appreciate the intensity of my efforts.

When the door swings open, I am forced backward in shock. There, clad only in a bath towel, is the old man, his face showing an intent to do battle even as it is obvious that he is in no shape to do so. He is weak and in obvious pain. Except to include a frown, his expression does not change when he sees that there is no one there, at least no one he can see. When finally he gives up and turns to reenter his condo, I recover enough to seize an opportunity that eluded me earlier. With more desperation than grace, I leap into the interior, in the process passing through the old man's body but banging against the door jam, the incongruity of this reminding me that this condo is real even if its occupants are not.

After giving the door a satisfying slam, the old man agonizes his way through the living room and into a bedroom off to one side. As I follow, I see no sign of the woman, nothing to indicate she is still there. Once in the bedroom, the old man rips off his towel and, throws it in disgust at the bed. I feel his anger, even as it diminishes to a level just above annoyance. He is troubled, and my pounding on his window has only added to this. As he goes about selecting clothes to wear, I have time to wonder at the miraculous change in his health, from practically non-existent to fighting-mad in a few minutes time. There is not even a redness of skin to lend evidence of a recent injection in his neck.

My blood chills as it comes to me just how little time has passed since I saw him lying on the sofa, too little time to undress, shower and dry himself. My blood chills even further as I watch him pull on a formal shirt then work his way into a tuxedo, tie and matching cummerbund.

For the second time in little more than a day, I am hit with an urge to flee this world of bad dreams. But I know I will not, that I cannot, that I have no choice but to bear witness to the remainder of this unlikely play.

The wait is less than ten minutes; the sound of a key turning in a lock begins the process. I know even before I look up what I will see. A woman enters, a young woman stunningly beautiful and wearing a red, short-sleeve, thigh-length dress and carrying a briefcase, large and dark gray in color. I watch in horror as the scene plays out for a second time, this one with me as a front- row spectator.

Still carrying her briefcase, the young woman, moves to his side then assists him in sitting up- he smiles, but it is not, as I previously thought, in appreciation of her help. He is sad, terribly sad, but out of kindness seeks to hide this from her. He knows what must take place this day, and he knows that as he leaves his own pain behind he will create pain in another. As I continue to stare I sense even more in his smile. He is fond of this woman, terribly fond, more so than their relationship, health-care giver to patient, would appear to warrant. And I see now that what I had interpreted as indifference in the woman is not that at all. Like the old man, she is putting forth a stoic face to hide the agony that lies just beyond it.

Above the smile a question appears in her eyes, a question the old man easily sees. There is a sigh in his voice as he offers himself for a final examination, one he knows is futile. I understand then that he fears, not so much what will happen, but what might fail to happen. He is hurting, hurting badly. The woman ignores all of this as she applies a stethoscope to his chest, the action gentle as if she recognizes the cruelty inherent in this delay. I find myself warming to her, even as I know what she is about to do.

She finishes her examination, removes the stethoscope from her ears, then straightens up, her eyes intent on those of the old man. She knows, as he does, that there is no need to comment further, yet she feels compelled to offer a word of... apology. I note a tremble in her hand as she then extracts the syringe and moves it into position. And when she plunges its point into the old man's neck, I sense that the discomfort in her stomach is equal to my own.

Although as anxious to see this to a close as he, the young woman is driven to a final word of comfort, one that promises a swift ending without pain. He returns her thought with a smile, the last he will ever offer. She depresses the syringe and he falls.

The satisfaction I imagined in this woman earlier is other than that. I see relief, relief that it is over. Relief that this old man no longer suffers, and that he experienced tenderness and human closeness at the end. Relief that she did not botch that most delicate of moments.

I feel relief as well, but I also feel the pain of loss. This old man meant something to me. His passing creates within me an emptiness that will not easily restore itself. I turn to stare at the woman who brought about his death, my feelings for her mixed and uncertain. I loath what she has done, but I love her for doing it. The uncertainty comes from my not being able to understand the why of this.

But the play has not yet ended. There is a final act, one designed to soothe even as it further confuses.

I watch as she grabs her briefcase, moves into the bathroom then, without preamble, begins removing her clothes, not bothering to close the door as she does so--there is no need; the old man will not see. As efficient in undressing as she is in dispatching people, in seconds she is naked and the twenties costume I so admired is safely tucked into a plastic bag, whatever contamination she saw in it now contained. Her body comes next, and this she accomplishes by means of a shower, the length of which testifies to the revulsion she must feel.

The feeling that there is more to this woman than the cold efficiency I saw earlier is reinforced. She is even crying, even as her expression, highlighted by a lean smile, otherwise shows satisfaction. By the time she steps out of shower, she is to me as much a victim as her recently-departed patient.

A lovely and very naked victim, as I have more and more difficulty ignoring--I am an unwitting voyeur to her most private moment. Yet I confess no disappointment in myself for how willing I am to stare. She is absolutely lovely, a grim reaper with a body that will tempt anyone to follow wherever she leads.

It comes to me then just how long it has tempted me. And what the incongruity of tears matched against a smile of satisfaction is trying to tell me.

I am in a dream of my own making, a dream prompted and perpetuated by emotions I could not or would not control. Even now, they are loath to give up; they release their hold on me, but do so at their own speed.

This floor and the people on it are the woman's accomplices, each with a role that means to instruct. The floor lays the scene, a variation of the one from which my mind retreated. The man in the corridor yesterday wore clothing of the future because in the future what took place today is likely to be considered reasonable, even commonplace. The old man wore formal attire because it was important to him, not that his life be prolonged, but that he leave it with a sense of dignity. The young woman wore clothes of the twenties because that is when I met her for the first time.

With great reluctance, I turn away from this lovely reminder of my past. As if synchronized to the turn, the room fades back to what it has always been, a bedroom, our bedroom, not on the eighth floor of a troubled imagination, but on the seventh floor of a building in which she and I have lived for many years. She lies on the bed not ten feet away, her looks tainted by age but no less appealing to me. An oxygen tube descends from her nostrils, and in one arm an IV drip is firmly attached--it contains morphine. She is dying, and she is in pain.

She smiles at me, even as her face shows an agony she wants so much to hide. There is a tear in her eye that matches the one in mine, and I bend to kiss it away, my movements slow and laden with feeling, not the fear and anxiety of earlier, but of love and loss. I touch my lips to her other eye then to her nose then to her mouth, the latter puffy from too much agony endured for too long a period of time. I am aware, as I am sure she is, that this ritual, so much a part of a long married life together, is being performed for the last time.

She cannot speak; her discomfort is too intense to permit this--my fault, as I could not bring myself to ease her out of her pain. But she expresses her love in other ways, by the tear, by the heroic attempt to put a smile where a grimace would more easily flow, by the tolerance and understanding in her eyes.

Unable to trust myself to delay, I turn, place a hand on the control that regulates the flow of morphine in her drip, then open it all the way. When I turn back, aware that her lovely face will soon exist only in my dreams, I am rewarded by another smile, slight and sad to be sure, but now including appreciation. It fades, as does the light in her eyes as she slips into long-awaited relief. I return the smile and the sadness that will forever be a part of it, then turn and walk away.

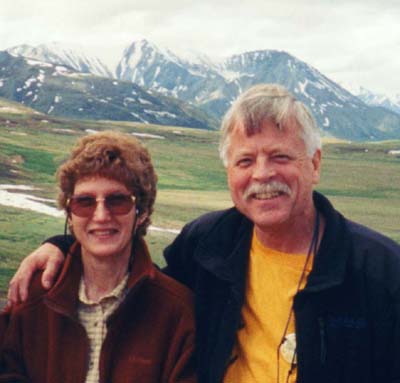

| The husband-and-wife team, Noel and Carol (using the surname, "Carroll") have produced novels and short stories in three genres: thrillers, science fiction and humor/satire. There is similarity between them, with all emphasizing story ahead of the sensational. Sensationalism also takes a back seat to plausibility, to reasonableness, to validity and purpose of character and to avoidance of the commonplace and the expected. The effect is to produce tales that seduce and engage readers of all genres. |

|

E-mail: noelcarroll@worldnet.att.net

URL: http://home.att.net/~noelcarroll

Visit Aphelion's Lettercolumn and voice your opinion of this story.

Return to the Aphelion main page.